Neighbourhoods on Google Maps aren't as official as you'd think

How do suburbs and neighbourhoods get their names? That seems to be changing in the age of Google Maps, according to an amazing story at The New York Times.

How do suburbs and neighbourhoods get their names? That seems to be changing in the age of Google Maps, according to an amazing story at The New York Times.

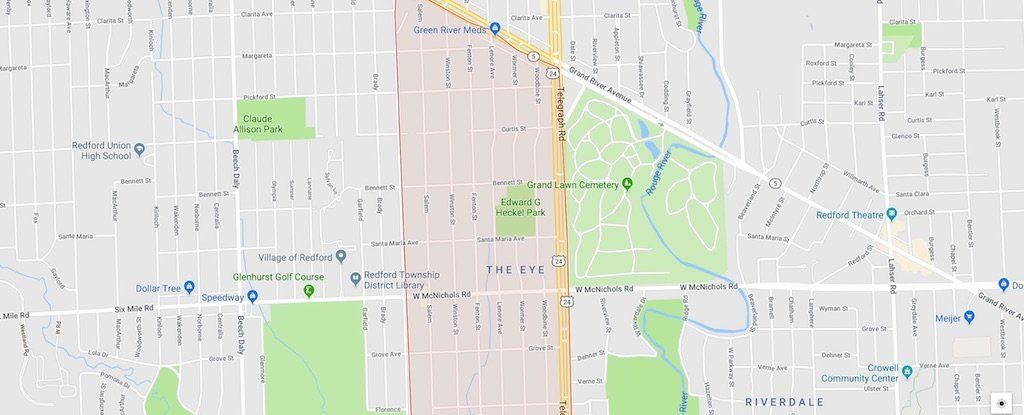

It seems there are some bizarre feedback loops taking place around how Google Maps gives names to areas of the maps, and then how people and businesses around such areas use these names because they saw it used at Google.

From the 'East Cut' in San Francisco, to 'Fishkorn' in Detroit, or yet more examples in Los Angeles and New York City, it seems that it takes very little verification to get a neighbourhood name updated onto Google Maps. And once there, people take these names very seriously.

'The East Cut' example turns out to have related to an effort to rebrand the neighbourhood by local area residents. But examples like Fishkorn seemed to be a transposition error, with letters switched by accident.

Another example suggested a real estate agent had listed a property adding 'Heights' to the end of an area name to fancy things up, and soon after Google Maps was now actually using this name on the map.

"Yet some submissions are ruled upon by people with little local knowledge of a place, such as contractors in India, said one former Google Maps employee, who declined to be named because he was not authorized to speak publicly."

In a world where something becomes true simply for existing on the internet, it's a tricky situation.

We often want people to stick to the trusted sources online when it comes to verification of what's real and what's not.

But when Google Maps - far and away the most used and trusted mapping tool online - is taking unofficial names and giving them bone fide status on its maps, we're in some weird waters.

In a fun footnote: Fiskhorn is indeed Fiskhorn again in the aftermath of this article. Seems like errors can be corrected quickly (after existing for a long time) once pointed out. But how many more are out there because no one has bothered asking for a fix yet?

Check out the full story over at The New York Times.

Byteside Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.